Tundra Swan History Tour

By Joe Kosack

PGC Information Specialist

PGC Photo/Hal Kober

|

The Tundra swan - Cygnus columbianus - is America's smallest

and most widely distributed swan species. Incredible travelers that cross the continent

twice annually as they migrate to and from wintering and nesting areas, tundra swans are

the continent's most abundant swan. Two other swans are found in North America: the

resurgent trumpeter swan and the introduced mute swan, which is despised by wildlife

managers. The future is brighter than it has been in a long time for trumpeters.

Unfortunately, the same appears to be true for the unwanted mute swans, too. |

| We owe Lewis and Clark for providing the tundra swan its time-honored and

possibly most popular name. On their march to the Pacific, the explorers, while in the

Columbia River region, happened upon large concentrations of swans. Most were a species

they named "whistling swans." The species was renamed the tundra swan only

recently. The tundra swan also was referred to by John J. Audubon as the "American

swan," a name given it by Dr. J.T. Sharpless of Philadelphia, whom Audubon apparently

believed was the true discoverer of the species. |

John J. Audubon's American Swan

|

The whistler's historical background in colonial America is somewhat hard to track. It

seems unlikely that America's enterprising colonists missed the family meal opportunities

one swan could provide. But mention of the birds seems to have eluded most early

historical records. The birds were considered sporting to hunt and were respected for

their alertness and strength.

John James Audubon

|

Audubon and possibly others recognized these swans as

transcontinental migrators in published ornithological accounts in the early 1800s. But

were whistling swans scientifically identified in the East prior to Lewis and Clark's

discovery on the Columbia River? Available references don't pinpoint when Dr. Sharpless

identified the American swan. But records clearly attribute discovery of the species to

Lewis and Clark. |

Audubon apparently was fascinated by the tundra swan. In his An Account of the Habits

of the Birds of the United States of America, he presented considerable information about

American swans, or "Cygnus americanus of SHARPLESS." Audubon seemed to be

reporting on the confusion surrounding the species. He even wrote about spending time

analyzing three swan specimens obtained in the Baltimore and Philadelphia areas. He used

rum to preserve the swan remains.

In his writings, which were published by Audubon, Sharpless went to great lengths to

describe the swan's toughness and wariness, particularly as it related to hunting, which

is no doubt how he and many other nineteenth century birders became familiar with the

species. He also noted that if they were less than six years old, swans, "are very

tender and delicious eating."

| Sharpless mentioned hunters led flying swans by 10 to 12 feet in front of

the bill when hunting them. Sometimes hunters got within shooting range of swans by

"sailing down upon them whilst feeding." Sharpless also noted another unique way

swans were collected: "In winter, boats covered by pieces of ice, the sportsmen being

dressed in white, are paddled or allowed to float during the night into the midst of the

flock, and they have been oftentimes killed, by being knocked on the head and neck by a

pole." |

Flying Swans

PGC Photo/Hal Kober

|

Historical swan references typically have hunting connotations because that's what

wildlife was used for by our forefathers, who often rationalized that the bigger the

animal, the more meals it could provide. Given the tundra swan's size - 10 to 18 pounds,

it was considered by many to be well worth pursuing. There seems little doubt that some

Pennsylvanians admired the grace and beauty of swans. But their observations weren't as

apt to be recorded.

Swan Song

|

The tundra swan is credited as the originator of the "swan

song," a call purportedly made by a mortally-wounded swan as it falls from the sky

and frantically tries to rejoin its flight companions. A "swan song," defined by

Webster's is, "a song of great sweetness said to be sung by a dying swan." It

would seem that the song's interpretation is relative to the listener perception or

imagination. But in our modern culture, at least, a swan song is typically a gracious,

usually memorable, farewell appearance. |

Tundra swans withstood the unregulated harvest most American wildlife species were

subjected to prior to the twentieth century. Valued for their down and flesh, tundra swans

were routinely taken by hunters, even market hunters. But the exploitation effort wasn't

as unrelenting as that which consumed the trumpeter swan. As the 1900s opened, tundra swan

numbers were down from historical average population levels. But there were few waterfowl

species that didn't suffer a similar fate. It was a sign of the times, another reason why

American wildlife conservation movement would soon begin. Trumpeters were in worse shape.

Trumpeter swans were decimated on their northern nesting areas in the mid to late

1800s. Unlike tundra swans, which nested in more remote arctic regions, trumpeters nested

in the northern United States, where they were subjected to unrelenting hunting pressure

by American Indians and settlers. Trumpeters, in fact, were killed throughout their

semiannual migrations, on their wintering grounds and while they nested. Hundreds of

thousands of swan skins and quills were exported to Europe in the mid 1800s to satisfy an

insatiable market. Even their cygnets were taken from nests. The pressure on the resource

was incredible.

| The improved season and bag limit protection afforded by America's

wildlife conservation movement and the protection provided by the U.S. Migratory Bird

Treaty likely saved these birds from extinction. The trumpeter's population decline was

slowed considerably. Still, by 1932, it's estimated there were fewer than 100 trumpeter

swans worldwide. Only through intensive management of nesting grounds were trumpeters

pulled from extinction's quicksand. For a time, though, it's fair to say the species'

collective neck was stretched to its proverbial limit. |

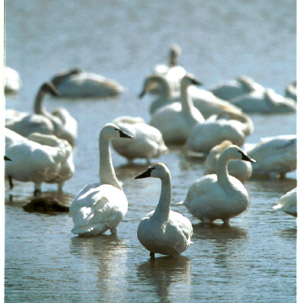

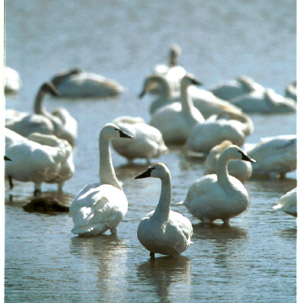

Tundra Swans

PGC Photo/Hal Kober

|

| In contrast, the tundra swan population slowly increased annually in the

East since about 1930. In fact, over the last two decades of the 1900s, it has grown

dramatically. Hunting is now seen as a way to help stabilize a growing population before

property damage problems become excessive. Currently only Virginia and North Carolina

allow hunting in the East. North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Nevada and Utah allow

tundra swan hunting in the west. |

Tundra Swan

PGC Photo/Hal Kober

|

Tundra and trumpeter swans were both listed as game species in the

Migratory Bird Treaty with Canada, signed in 1916. Prior to the treaty, swans were a

huntable migratory bird species in America and Canada. After the Treaty was signed, no

open seasons were declared on either swan species until Utah was permitted to hold a

limited experimental hunting season on whistling swans in 1962. From 1970 to 1981, three

states permitted tundra swan hunting: Utah, Montana and Nevada. North Carolina started

hunting tundra swans in 1984. Virginia began hunting tundra swans in 1988; it issued 600

permits that year. |

Since the mid 1960s, the North American tundra swan populations appear to have at least

doubled, according to some researchers. The eastern wintering population numbers 90,000 to

100,000; the western, 60,000 to 70,000. In 1999, 6,900 hunters reported taking about 3,600

swans from the eastern population; in the West, 3,300 hunters, took about 1,400 swans

(including some trumpeters).

| The future is brighter for tundra and trumpeter swans now than it's been

for a long time. Populations of both species are stable or growing. Neither is considered

threatened or endangered. Wildlife management agencies also have started research to learn

more about swans. America will probably never again have swan populations similar to those

of colonial times. But it seems safe to say that swans will grace our waterways and

seasonal skies for generations yet to come. There truly is safety in numbers. |

Swan Research

PGC Photo/John Dunn

|